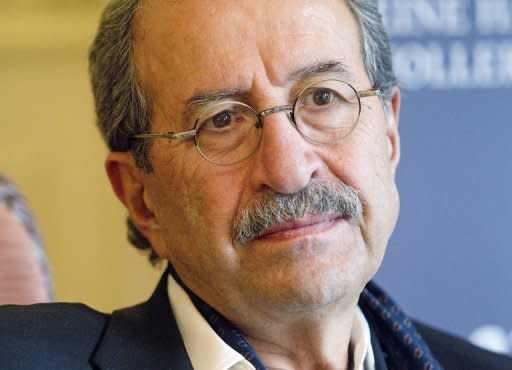

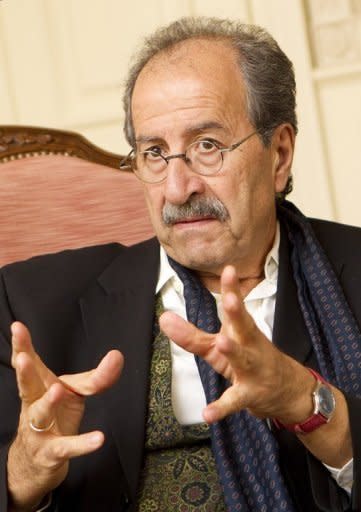

Author Rafik Schami fears for post-Assad Syria

Seated in a plush Vienna hotel, Rafik Schami is half a world away from the unrest tearing Syria apart. But that doesn't stop the author caring and worrying deeply about the country he fled 41 years ago. Even in the best-case scenario, the award-winning Schami told AFP in an interview, creating a democratic Syria once "dictator" Bashar al-Assad has gone will take at least a decade of "sweat and tears," The situation "is more dangerous than in Iraq," says the 66-year-old author, whose books have been translated from German -- the language that he writes in, that of his adopted homeland -- into 24 languages. But because Syria's population is more diverse than Iraq, which was plunged into years of sectarian violence after the US-led invasion in 2003 that ousted Saddam Hussein, Schami sees a glimmer of hope. "I am not naive but I think that if we are lucky, we will need 10 years. We are not Tunisia, it's going to take more than three weeks to become democratic," he says. "It will be 10 years of reconstruction, of stretching out the hand of reconciliation to heal all the wounds between families. There is now hardly a single family that has not experienced loss." Creating a functioning, modern society will take billions of dollars, money that should come from Arab states to pay for European technology and help build up democratic institutions from scratch, he says. "I don't envy the new government. No one is going to give them flowers," says Schami, whose awards include Germany's Hermann Hesse Prize and the Chamisso Prize. "This is why the term 'Arab spring' is wrong. This is no walk in the park with little bunches of flowers. No, this is going to take work, sweat and tears." Having lived in Germany since 1971, where he now lives in a village "with 1,500 inhabitants and 2,000 pigs," Schami says he has no plans to move back to Syria once Assad's regime has fallen, although he says he has been asked to play a political role. But he hopes to visit and to give readings from his books because literature, he believes, can also help Syrians find peace. Novelists "cannot provide political solutions, but we can provide comfort, we can write stories about forgiveness, stories about the enemy to show that they are human," Schami says. "Literature can help by creating new people, a person of freedom, a person of forgiveness, a person with a heart." Under Assad, and during the three decades of rule by his late father Hafez al-Assad, writing was a dangerous occupation, Schami says. This comes across in one of his best-known books, the semi-autobiographical "Eine Hand voller Sterne" ("A Handful of Stars") -- 100,000 copies of which were handed out free in Vienna this week as part of the annual "Eine Stadt, ein Buch" event -- about growing up in Damascus and wanting to be a journalist. "Writers were able to publish, but you had to be careful, and authors had 'scissors in their heads.' Because of censorship, people began to censor themselves," he says. "Caution and literature don't mix well. Either it is fresh and written in total liberty, or it's nothing," Schami says. "You could get five years for a poem and be humiliated by primitive torturers who can't read." Schami, who says that as an old imperial capital Vienna "reminds him of Damascus," talks as if Assad has already fallen. This is because this is now inevitable, he says. He has too much blood on his hands to play any role in Syria's future. "He is the commander-in-chief and he bears the responsibility," Schami says. "It's finished for him now... I am slowly coming to the conclusion that he can no longer escape with his life."