Philippine mining reforms ignored at gold-rush site

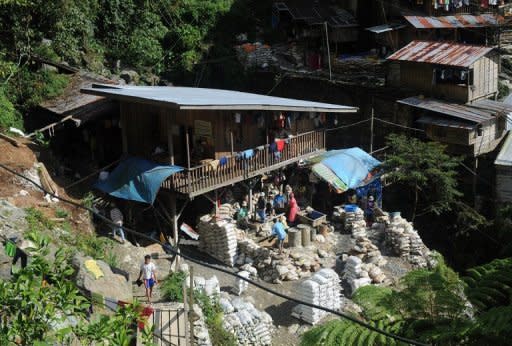

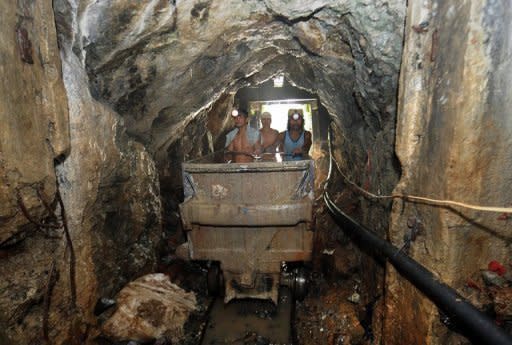

The Philippine government wants to close thousands of small-scale mines blamed for environmental devastation, but Reynaldo Elejorde insists his chaotic gold-rush mountain town will survive. The 53-year-old former carpenter and his family have been digging alongside hordes of others into the rich veins of Mount Diwata since the 1980s, and the efforts have allowed them to survive just above the poverty line. "We will insist that we stay here because this is our only livelihood," said Elejorde, dressed in a dirty T-shirt and shorts with a flashlight tied to his head as a makeshift mining lantern, during a typical day of hard toil. President Benigno Aquino announced mining reforms last month that his government said would better regulate a chaotic industry, improve environmental standards and deliver a bigger share of revenues to state coffers. Part of the planned reforms would ensure more strict government supervision of places such as Mount Diwata, a product of a unique Philippine law dating back decades that allows individual miners to set up their own operations. A tribesman's discovery of gold in what was then a logging area in 1983 started a mad scramble to Mount Diwata of labourers, farmers, ex-soldiers and former guerrillas from all over the country, all seeking to get rich. Today scores of tightly packed houses made of scrap wood and roofed with tin sheets or tarpaulin sit on the mountainside, many of them built over tunnels that the homeowners excavate. About 42,000 people live on and around the mountain, according to the village census, but residents say the population swells and the honeycomb of tunnels get busier when the price of gold rises. The site is just 70 kilometres (43 miles) north of the major trading city of Davao, but it can be reached only through muddy roads and it has earned a reputation as a lawless "Wild West" site. The government's small-scale mining provisions were originally intended to give poor, mainly rural people a chance to earn a little money, according to the head of the government's Mines and Geosciences Bureau, Leo Jasareno. But it has been widely exploited and most of the small-scale miners today, including those in Mount Diwata, violate the conditions for small-scale mining by using explosives and poisonous chemicals such as mercury, Jasareno said. Jasareno estimated that there may be as many as 300,000 such small-scale miners across the country, creating a major environmental problem. With few safety regulations, workplace deaths also occur frequently. At Mount Diwata, five people were reported killed in a landslide in December last year. "The executive order (Aquino's mining reforms) will address all the problems in small-scale mining. Environmental problems will be addressed as well as safety," Jasareno told AFP in Manila. Some of the key reforms will be to restrict small-scale operations to "community mines", so that they can be more closely supervised, while others deemed to be dangerous or bad for the environment will be closed. But at Mount Diwata, community leader Franco Tito said miners had seen similar efforts from previous governments come and go, with no effect. "It is just a duplication of past presidential orders, local ordinances, republic acts, special laws and what have you, which are basically telling us to stop the mining activity," he said. Tito said he suspected the national government's real agenda was to hand the mountain's resources over to a big mining company, and that the miners would resist any effort to move them. The local province's governor, Arturo Uy, said he supported Aquino's mining order but he also questioned whether it could be applied in his domain. "We cannot just tell them (the miners) to move out as they are so many. You can expect protests and rallies because they won't allow the mining operations to go the large mining firms," he said. Uy said he had previously proposed a designated area for small-scale miners, similar to Aquino's order, but that it never took off "because they (the miners) wont listen". However Clemente Bautista, president of Kalikasan (Environment), a green political party operating in the area, said local officials tolerated illegal activities because they also benefited from them. "Basically, the corrupt government officials profit from that. The provincial officials have a stake in mining. They have interests in the operations," he told AFP in Manila. But he acknowledged that resistance from the miners would also intimidate officials from taking action. "The small-scale miners will fight back. You cannot force them out if their alternative is that they go hungry," he said.