Warlords enslave huge armies of child soldiers

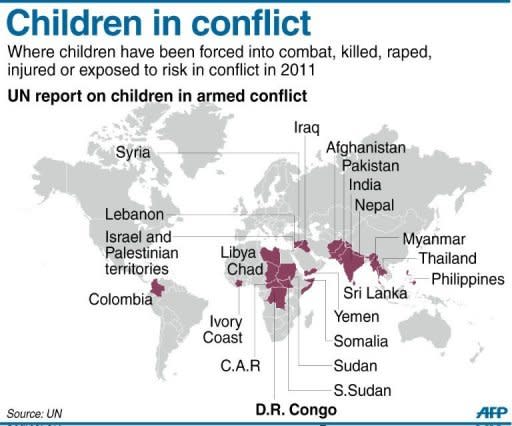

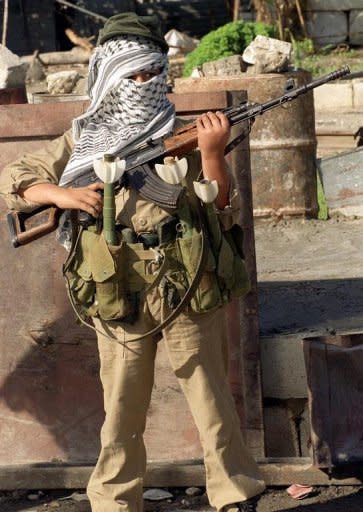

More than 11,000 child soldiers were freed from military slavery last year, but the United Nations believes hundreds of thousands around the world remain at the mercy of warlords like Thomas Lubanga. The 14-year jail term ordered against Lubanga by the International Criminal Court on Tuesday is a "historic" signal, according to Radhika Coomaraswamy, who ends a six-year term this month as UN special representative on children in conflict. The crime of recruiting and using children as soldiers "is now written in stone, nobody can say they are unaware of it," Coomaraswamy told AFP in an interview. Governments are starting to get the message. Only Lubanga's native Democratic Republic of Congo and Sudan are holding up a UN target to rid all government armies around the world of child soldiers by 2015. The UN believes hundreds of thousands of children are forced to fight at gunpoint by the likes of the Taliban in Afghanistan, notorious Congo warlord Bosco Ntaganda, the Shebab in Somalia, Ansar Dine in Mali and other terror groups and private armies around the world. Under-age combatants have existed for time immemorial. Alexander the Great trained as a child soldier, and desperate armies in both world wars enlisted and coerced youth fighters. But the practice has only been on the world "radar" for the past 20 years, said Coomaraswamy. "Mr Lubanga is the classic case from the Great African wars of the 1990s which was basically child abduction, the use of drugs, children used as soldiers, so he is as bad as they come," the UN official said. In civil wars around the world, drugs have been used to turn children against their families. Young girls are turned into sex slaves, or soldiers, or both. Coomaraswamy attributes her successes in fighting the scourge to the use of UN Security Council threats of sanctions against unwilling states and naming and shaming in annual lists. On top of the thousands of child soldiers released last year, 19 "action plans" have been signed with governments and groups, the UN representative said. Myanmar signed a deal after five years of talks. Thousands of children are believed to be in the government army and ethnic militias. The Somali government signed an accord this month to rid its ranks of troops aged under 18. Chad was another deal that took some tough talking. Coomaraswamy is confident that DR Congo and Sudan will follow. "Now I think we are on track that by 2015 we will no longer have any national army anywhere in the world that recruits children." Governments can generally be trusted to keep their word once they sign. "They don't like to be on any Security Council list or with the threat of sanctions hanging over them," the UN envoy said. Uganda was on the UN blacklist, but signed an action plan in 2007. "Now they have been delisted and are at the forefront of fighting the LRA," said Coomaraswamy. Lord's Resistance Army chief Joseph Kony, like Ntaganda in DR Congo, is wanted by the ICC. With groups like the Taliban and Shebab, which are "just very contemptuous of the international community" and refuse to negotiate, the only response is public appeals and mobilizing local populations against the groups, Coomaraswamy said. Community action in Afghanistan has brought down the number of attacks on schools. Peter Wittig, Germany's ambassador to the UN and chairman of the Security Council working group on children in conflict, paid tribute to Coomaraswamy's work and said tougher action may have to be considered. "We have to look at the next steps: how do we deal with rebel groups in various conflicts who persistently continue to recruit child soldiers? Perhaps we have to push the envelope further and apply the whole range of instruments at our disposal," Wittig said. "In our view there must be strong and sustained pressure on those who resist to comply with international law," he added, indicating this could include "the establishment of an additional sanctions regime."